It’s Time for Women to Redefine the World of Motorsport

- Mikaela

- Nov 2, 2018

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 12, 2021

“The war that has been raging in the media is not a simplistic war against women but a complex struggle between feminism and antifeminism that has reflected, reinforced, and exaggerated our culture’s ambivalence about women’s roles for over thirty-five years.” (Douglas, 2009)

Since the late 1960’s women have been fighting for equality between the sexes, fighting for equal rights in both the workplace and domestic environments. The fight for women’s liberation is one that throughout history and today still challenges and contests the stereotypes placed around women and their roles. The world of motorsport is one that is largely dominated by males, both on national and international levels.

Despite the gender stereotypes, history shows that women have been competing in motorsports for well over a century. The world’s first ever (documented) female motorised vehicle race was held in 1897 in Paris, France with eight French women racing on motorised tricycles around Longchamps horse racing track. This race occurred only 30 years after the first ever recorded motorised race in 1867. Women may have not raced first but they were there almost right from the start, until now and along this whole journey they have fought every step of the way to be on that top step right next to the men in motorsport.

If you conducted a quick survey of motorsport viewers and fans asking them to name any female motorsport competitors, it is more than likely going to be a concise list of recycled names like Danica Patrick (NASCAR), Maria Herrera (Moto3/MotoE), Ana Carrasco (World Supersport), Kiara Fontanesi (WMX – Women’s Motocross), Simona De Silvestro (V8 Supercars), and Renee Gracie (V8 Supercars). These are the names of great women, but they are also the names of the women who feature most in internationally broadcasted motorsports.

There are a multitude of different racing levels and competitions, not all of which are televised locally, nationally or internationally. Pamela Creedon states in her book ‘Women, Media and Sport: Challenging Gender Values’ that “The women’s sports coverage that does exist can be categorised in three ways: less coverage than men’s sports, greater coverage devoted to “feminine” sports such as tennis and golf, and coverage of athletes according to sex-role stereotypes rather than sports roles (Boutilier & SanGiovanni).”

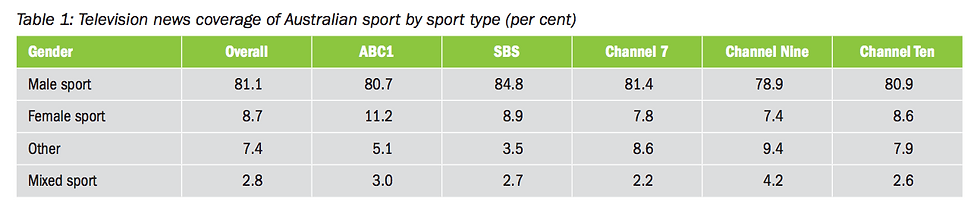

On the surface of motorsport history, it would seem as though there aren’t very many female competitors other than the big names of those who have won races or championships in their respective sports. Female motorsport competitors, even the big names are often overlooked due to the never-ending list of male competitors and their achievements, but this oversight can be blamed solely on the lack of media coverage for women’s sporting events. In a report by the Journalism and Media Research Centre at the University of New South Wales compiled for the Australian Sports Commission they found that women’s sport only takes up 9% of the overall sports coverage on Australian television, compared to 81% taken up by male sports.

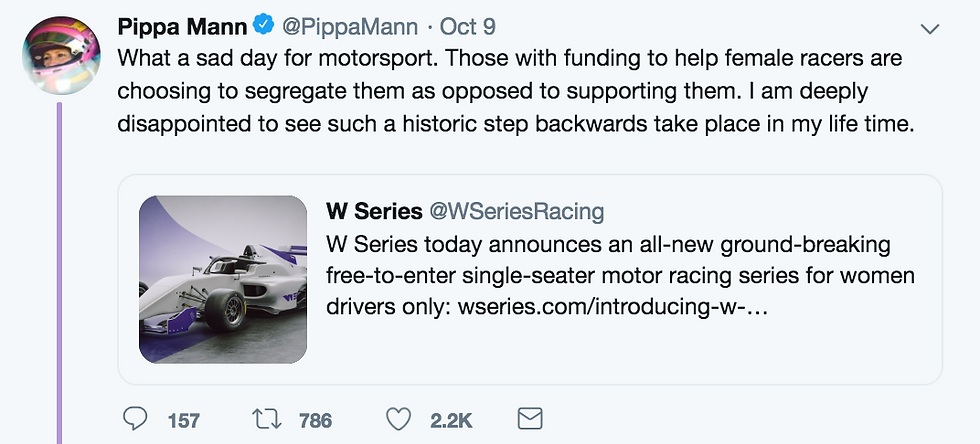

Hoping to be televised is the all new ‘W Series’ a free to enter, female only racing series to begin in 2019 supporting the Deutsche Tourenwagen Masters (DTM) touring car series in Europe, eventually moving on to include rounds in America, Australia and Asia. The purpose of the W Series is to provide women with the chance to hone and develop their skills as drivers without having to worry about funding.

In a statement on the W Series website, CEO Catherine Bond Muir outlined her hope for the series, “There are just too few women competing in single-seaters series at the moment. W Series will increase that number very significantly in 2019, thereby powerfully unleashing the potential of many more female racing drivers.”

The series will consist of 18-20 drivers whom have all gone through and passed the intensive pre-selection trials and testing. Those who make it into the series will receive training in multiple different aspects of the sport including driver training, along with media skills, fitness, racing simulators and technical engineering. The current prize pool for the competition is US$1.5 million (AUD$2,083,425), the winner of the series will take home US$500,000 (AUD $694,475) with the remainder of the money to be split accordingly right through to 18th in the end of season standings.

The launch of the series has received mixed feedback, from both motorsport fans and professionals alike. Majority of the backlash came from those who don’t support the segregation of the series, and want to see female drivers instead be supported in the professional feeder series (F4, F3 and F2) alongside male drivers, all the while pushing them closer to Formula 1 (F1). No one at W Series was able to provide a comment on whether the series is open to international applicants or if it is only accepting those from European countries.

When questioned on the possibility of having a similar series for female motorcycle racers, Australian motorcycle rider Rachelle Wilkinson said, “I don’t know about all female racing because if you ask most women that do race, they are quite happy to race against the blokes. It’s not an us vs. them thing. It’s about supporting them over every discipline and every aspect of motorsport.”

Another one of the common comments made about the new series was that it should be aimed at a younger audience, providing training, skills and funding to young girls who want to start their racing careers in karting. These kinds of series is prominent in the Grand Prix Motorcycling world with the Red Bull Rookies Cup, CEV Repsol Junior World Championship, IDEMITSU Asia Talent Cup and most recently the Oceania Rookies Cup.

All of these junior championships are open to both boys and girls, aged 11-16 from all nations to apply but most predominantly feature riders from the countries the races are held in whether that is Europe, Asia or Australia. The Oceania Rookies Cup will debut in 2019 with six rounds all to coincide with Australian Superbike racing series.

“It’s a really great new initiative to create pathways for the juniors. The kids will get to start learning properly, get coached and get trained and build them up through the ranks. Hopefully it will open up more opportunities for the kids within Australia and overseas.” said Liz Galazkiewicz, Events Organiser for Road Racing at Motorcycling Australia.

The Oceania Rookies cup will be a new and essential pathway for the youth of Australia that want to find their way into grand prix motorcycle racing. Much like the Asian and European junior series’, it will allow these kids including young girls to take the opportunity and the chances without having to up root their entire lives.

From the moment we’re born we are being molded to fit into a certain way of life, one the world deems appropriate for girls and for boys. Young girls are taught that they are fragile and that they aren’t supposed to do certain things because it’s not girly or lady-like but there are so many women out there breaking that mold. Women who are slowly coming out of the shadows of men and saying anything you can do, I can do and probably do it better.

This year Ana Carrasco became the first ever female road racing World Champion, taking the title for the World Supersport 300 series against 37 male competitors. The W Series may not be the most popular solution to a lack of women in the top classes of motorsport, but it is a start. It is a conversation that will continue on like it has for years already but this time we’ve got the women out there smashing records, changing history and putting us on the front page. The 21st century is a new era for women in motorsport, and it looks like we’ve got the throttle open and our foot to the floor.

Sources

Primary

Liz Galazkiewicz – Events Organiser – Road Race, Motorcycling Australia

Rachelle Wilkinson – Motorcycle rider

Secondary

Archibald, J. (2017). The Comprehensive Guide to the Formula One Ladder. The News Wheel. Retrieved from http://thenewswheel.com/the-comprehensive-guide-to-the-formula-one-ladder/

ASBK. (2018). About – Oceania Rookies Cup. Australian Superbike Championship. Retrieved from https://www.asbk.com.au/about-asbk/oceania-rookies-cup/

Blackman, B. (2010). When was the first motor race held?. Retrieved from http://anarchadia.blogspot.com/2010/01/when-was-first-motor-race-held.html

Caple, H., Lumby, C. and Greenwood, K. (2014). Towards a Level Playing Field: sport and gender in Australian media [PDF]. University of New South Wales Journalism and Media Research Centre and Media Monitors joint research for the Australian Sports Commission. Retrieved from https://www.dca.org.au/sites/default/files/towards_a_level_playing_field_-_updated_version.pdf

Creedon, P.J. (1994). “Women, Media and Sport: Challenging Gender Values”. (pp. 159-180). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Douglas, S.J. (1994). Where the Girls Are: Growing Up Female with the Mass Media. New York: Random House.

Harris-Gardiner, R. (2017). Fast Females: The First Recorded Ladies’ Race (1897). Retrieved from http://essaar.co.uk/fast-females-first-recorded-ladies-race-1897/

Kawasaki. (2018). Carrasco Wins Worldssp300 After Incredible Season Finale. Kawasaki Racing News. Retrieved from https://kawasaki.com.au/racing-news/carrasco-wins-worldssp300-after-incredible-season-finale/

W Series Limited. (2018). Introducing W Series. W Series. Retrieved from https://wseries.com/introducing-w-series/

Comments